Happy Tuesday!

Join me this week for a drive-by look at how Uber and Lyft run quality control on drivers and passengers on their platforms and try to earn trust themselves in the meantime.

But first, some news:

Google doesn’t have 2020 vision

Article: Emily Glazer + Patience Haggin / WSJ

What happened: in the aftermath of Russia’s 2016 election interference, digital ad companies like Google and Facebook committed to track and disclose more information about political ad spending on their platforms. Nearly a year later, Wall Street Journal reporters spoke with campaign staffers and consultants about Google’s database and discovered that it’s “fraught with errors and delays.”

Why it matters: Russia, 2020. The missing ads were identified largely because people — a.k.a. opposing campaign staffers — were actively looking for them. But what about actors who want to stay hidden? Google tracks ads by political campaign, not by issue, and since many of Russia’s 2016 efforts targeted specific social issues (e.g. Black Lives Matter), election watchers are concerned that Google might miss certain foreign influence efforts again this time around.

What’s next: unclear. Rep. Adam Schiff has warned that American lawmakers, tech companies and the public are not prepared to deal with foreign influence in the 2020 election. Schiff plans to hold a hearing on election security following Congress’ August break, while a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on antitrust (in which a Google representative was set to testify) was postponed. Google hasn’t announced any specific changes to its political ad tracking operations.

FaceAppAccess

Article: Davey Alba / Buzzfeed

What happened: FaceApp, a photo-editing app that uses AI to make people appear older or younger, has gone viral. However, it has also raised privacy concerns and questions about its Russian developers’ motives.

Why it matters: fears that FaceApp’s developers are sharing images with the Kremlin appear unfounded — so far — but the data privacy implications are still very real. The app’s terms give its developers a “perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, fully-paid” license to use your photos once you upload them. FaceApp hasn’t abused those terms yet, but nothing’s stopping it from doing so. Also, Alba notes that this type of license is pretty much standard practice, cautioning that “we’re far too quick to jump into something fun without thinking about the implications of giving up our data.”

What’s next: probably not much. But, if you’re concerned enough to check up on which permissions you’ve granted apps, learn more about what to look for: iOS users / Android users.

And now, on to Uber and Lyft…

Drive-share

Are you among the 36% of Americans that have used Uber, Lyft or similar ride-hailing apps to get around? Or maybe you’ve even followed these companies closely in the news, catching headlines about Uber and Lyft going public, riders being killed and assaulted by drivers, drivers being assaulted by riders, or the intense fight developing over driver pay and employment status.

Each has implications for the public’s overall trust in ride-hailing companies, but most approach these stories as riders — few have a solid understanding of how things work for drivers. Aside from those who have driven for a ride-hailing service or work in a related industry, our interactions generally involve calling a ride, chatting with the driver during the ride (or not), and then rating and/or tipping them afterward.

But drivers’ relationships with these companies* — as well as riders — are much more complicated, a fact that’s masked by the (apparently) simple process we take part in after finishing a ride. Even a discussion limited to driver issues could touch on declining pay, effects on mental and physical health, employment status and benefits, lack of professional development and support, and autonomous vehicles, just to name a few.

For this issue though, I want to focus on an aspect of the driver experience that most riders only know on a surface-level: five-star rating systems. I’ll explain how they work and how they aim to signal trustworthiness.

*Uber and Lyft are often referred to as Transportation Network Companies, or TNCs. While this issue will focus mainly on Uber and Lyft, I’ll use “TNCs” when talking about ride-hailing services generally and company names when something applies specifically to them.

First, some background

Before rider and driver ratings even come into play, there’s another tool TNCs use to ensure quality on their platforms: background checks. This step is crucial for several reasons.

Outsourcing verification

Background checks allow TNCs to offload a substantial amount of the work required to verify the trustworthiness of drivers. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that — many companies have similar hiring processes. But it involves an important distinction: riders aren’t just trusting the TNC to vet its drivers properly. Instead, they’re trusting the TNC to choose a competent background check service to vet its drivers properly.

As it turns out, outsourcing that work has led to problems. Unlike taxi companies, which require drivers to cover the cost, Uber and Lyft pay to run checks, incentivizing them to prioritize cost-cutting and speed. Uber, Lyft and Sidecar did exactly that, lobbying aggressively against laws requiring TNCs to run background checks at the same level of rigor as taxi companies, which would have cost more money but might have also caught more criminal offenses by drivers.

Download.com’s Shelby Brown also reported that Uber and Lyft have relied mostly on budget services such as Checkr, Hirease and Sterling, which are often less robust and have had issues with accuracy. Checkr alone has been sued at least 40 times over inaccurate reports.

Opting for cheaper background checks has come with tangible costs for riders. A 2018 CNN investigation found that at least 103 Uber and 18 Lyft drivers had been accused of sexual assault, 15% of drivers failed state background checks in Massachusetts despite passing checks by Uber and Lyft, and both companies settled lawsuits alleging they misled customers about the nature of their background checks.

In response to recent rider safety issues, both Uber and Lyft have implemented new in-app safety features and “continuous” background checks (i.e. using technology to more quickly identify new criminal charges against drivers).

It’s difficult — and likely too early — to tell whether these new strategies are working. Outside observers have frequently been frustrated by the lack of publicly available data on TNCs, whether relating to violent crime, driver pay, taxes or other public policy matters.

In fairness, with a platform the size of Uber or Lyft, it’s impossible to keep all bad actors out. And the recent high-profile murder of an Uber rider in South Carolina wasn’t actually committed by an Uber driver, but rather by someone posing as one.

There are also tough questions about who should or shouldn’t be allowed to participate on gig economy platforms — whether driver or rider — and any policy is ultimately a balancing act. For example, when deciding which types of past criminal convictions disqualify someone from driving, TNCs must weigh rider safety with unfairly denying work to individuals based on crimes that are irrelevant to driving or were committed years earlier.

It’s worth noting here that the vast majority of drivers have not committed violent crimes and that no one has definitively shown that TNC drivers are any more crime-prone than taxi drivers or the general public. Further, improving background checks and safety features isn’t up to drivers, it’s up to the TNCs.

Passengers get a pass

For all the work TNCs are doing to improve background checks for drivers, riders don’t undergo a similar vetting process — you only need a smartphone and credit card to sign up.

Companies setting unequal requirements for each party is a recurring theme with two-sided platforms. Often, one side of the marketplace has more economic leverage, as is the case with Uber and Lyft riders. Like other tech companies that have prioritized user growth over profitability, Uber and Lyft have kept it easy for riders to join and stay on their platforms, while the reverse isn’t true.

That asymmetry can have serious consequences for drivers. The Guardian’s Michael Sainato investigated multiple cases where passengers sexually or physically assaulted female drivers, finding that:

In each case, the drivers felt Uber and Lyft offered little to no assistance or support, and that current company policies are inadequate.

Both companies have 24/7 support teams dedicated to handling incident reports. Still, drivers are looking for additional protections and for TNCs to vet riders before they’re even able to get in the car.

I’ll take a deeper dive into background checks (on both sides of platforms) in a future issue, but for now, let’s turn to ratings.

On a scale from 1 to 5...

Uber and Lyft calculate driver and rider ratings slightly differently (bolded below). Here’s the breakdown:

Uber Driver Ratings

The math: on a 1-5 star scale, the average of their last 500 ratings, not including…

Trips canceled by the rider

Trips not accepted by the driver

Rides where the rider didn’t rate driver

Rides where the reason for a rider’s negative was out of the driver’s control

The mechanics:

Ratings are submitted anonymously

Riders have 72 hours to rate drivers and aren’t required do to so (whereas drivers must rate riders immediately before accepting their next ride)

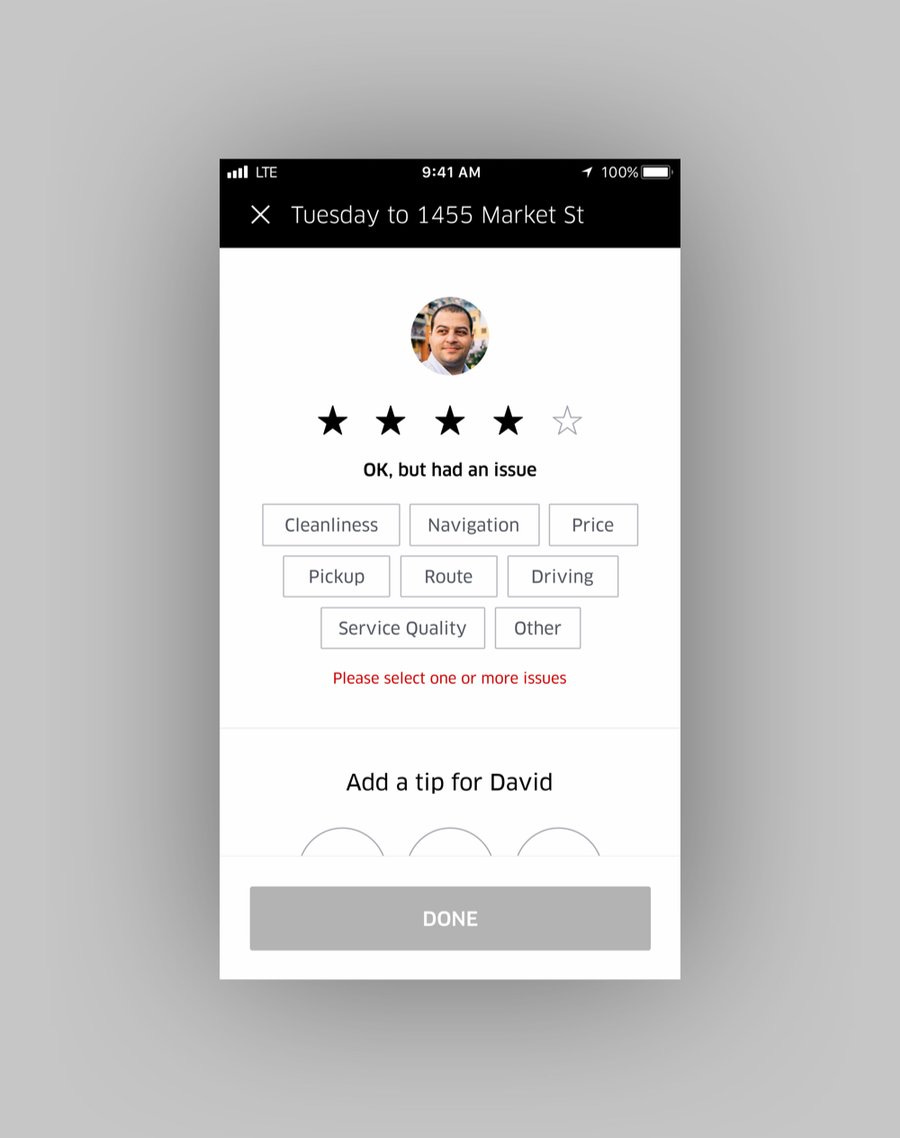

When riders rate drivers below five stars, they must select a reason why (to help Uber determine whether things were out of the driver’s control)

Riders and drivers who rate each other less than three stars won’t be matched again

Neither side sees any changes to their own score until they’ve rated the other person, as to prevent retaliatory ratings

Drivers receive warnings from Uber when their ratings drop below average and risk being deactivated if they stay below (that average varies by region, but Business Insider obtained documents showing that 4.6 seems to be a pivotal number)

Lyft Driver Ratings

The math: on a 1-5 star scale, the average of their last 100 ratings, not including…

Trips canceled by the rider

Trips not accepted by the driver

Rides where the reason for a rider’s negative was out of the driver’s control (upon further investigation by Lyft)

The mechanics:

Ratings are submitted anonymously

Riders have 24 hours to rate drivers, but if they don’t, drivers automatically receive five stars

Drivers still must rate riders, but with Lyft, they have 24 hours to do so

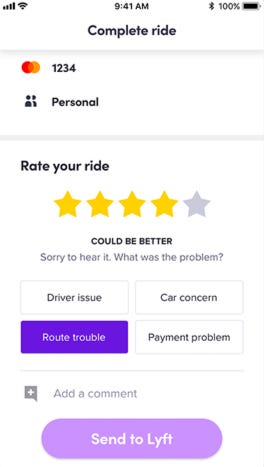

When riders rate drivers below five stars, they must select a reason why

Drivers can request to change a rating they gave to a rider or have a rider’s rating removed if they find it unfair, which Lyft may or may not agree to

Lyft encourages drivers to stay above a 4.8, with a similar warning about possible deactivation if drivers linger below that average for too long.

What’s the takeaway?

Each of these design decisions is a balancing act aimed at ensuring both riders and drivers have a positive experience with the app. But unless riders and drivers both have a clear understanding of these rating systems — i.e. these design choices and incentive structures — that balance can be hard to achieve.

For example, it’s probably news to most riders that anything below a 4.6 is essentially a failing grade — something drivers have frequently complained about. In response, Uber has begun providing riders with more information about what each rating means, as well as requiring feedback on four-star or lower ratings in hopes to improve consistency across riders’ ratings. Uber also recently announced it would start deactivating riders with “below average” ratings to deter bad behavior from riders, who previously didn’t have much incentive to keep their score up, though its unclear whether they’ve taken much action on that policy yet.

For its part, Lyft is now giving drivers five stars automatically unless riders intervene to rate them lower. Lyft has also tried to make the driver- and rider-facing rating process more symmetrical (e.g. allowing each side 24 hours to submit ratings).

Many of these changes were inspired by drivers themselves. Both Uber and Lyft have created driver advisory groups, though these have been criticized as mere PR responses to increasing coordination and demands from driver advocacy groups around pay rates and benefits.

Tip-ical

Before leaving this topic, I have to mention tipping. While not a direct indicator of trust, it’s closely related to the rating system, accounts for a non-inconsequential amount of driver pay, and is similarly affected by subtle design decisions.

Uber did not historically allow tipping, and only added that as a feature in 2017, while Lyft was much earlier to the game. Additionally, Lyft announced an option for riders to set a default tip amount and reminds riders to tip and rate drivers when they re-open the app after a ride (say, because they were in a hurry when they hopped out of the car).

These may seem like minor distinctions, but like the little red notification bubbles on apps, user interface choices can work wonders on people’s subconscious and emotional levers.

Sergio Avedian, a contributor at RideShareGuy and long-time TNC driver who I spoke with for this issue, explained how those differing approaches have played out:

Tipping is something people are conditioned to do — it doesn’t happen automatically. If I take 100 rides with Lyft, 30 people might tip. With Uber, maybe five.

In other words, because there wasn’t originally an expectation for Uber riders to tip, they became accustomed to not doing so. Simply adding a tip option didn’t necessarily change their behavior.

One idea Avedian proposed as a remedy: an automatic 10% tips on all rides.

Ride or die

Uber and Lyft riders (or drivers), what are your thoughts? Did you know a 4.6 was a bad rating? Would you stop using a TNC that automatically tipped drivers 10%? Let me know!

First time reading Trusty? Subscribe below!