Hey Trustees!

You may have heard that journalism is in a financial crisis. Revenues, circulation and employment have all declined in recent years. There are multiple factors at play, but the most significant is technology’s impact on the business models that have traditionally funded journalism.

So, when the Wall Street Journal reported last week that Facebook is working on a dedicated News Tab and wants to pay news publishers “millions of dollars a year” for their content, it should have been welcome news. Instead, many in the industry reacted with skepticism.

Why does this matter if you’re not specifically involved in the business of news?

Approximately 170 million Americans use Facebook, and according to Pew, 68% of them — 116 million — get news there. However, 57% of that group believe the news they find on social media is “largely inaccurate.” In other words:

66 million Americans get news from Facebook despite not trusting the accuracy of that news.

Neither publishers nor users trust Facebook, yet both are deeply dependent on the platform. So, whether you’re a Facebook user, journalist, or concerned citizen, it’s worth taking a closer look at Facebook’s plans to “help people get trustworthy news and find solutions that help journalists around the world do their important work.”

In this issue, we’ll explore those plans, get to the root of publishers’ distrust, and talk about how this change could impact both the news you consume and the outlets that produce it.

But first, some news:

About face

Article: Kaveh Waddell / Axios

What happened: In Axios’ Future newsletter, Kaveh Waddell writes that, at least with “manipulated media” (such as deepfakes), tech companies “are considering a fundamental shift with profound social and political implications: deciding what is true and what is false.”

Why it matters: as I discussed in last week’s issue, tech companies are facing increasing pressure to take more active roles in limiting the spread of misinformation via their platforms. AI-generated content is one area where, if Waddell’s reporting is correct, tech companies looked poised to start doing that.

What’s next: Waddell’s sources include experts from two nonprofits, WITNESS and Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. As lawmakers think through these complicated issues, expect them to continue to rely on experts from similar organizations. As always, follow the money — sometimes the “nonprofit” label can mask an organization’s agenda.

Twittervention

Article: Angela Chen / MIT Technology Review

What happened: Twitter announced Monday that it will no longer allow ads from “state-controlled news media entities.” The move came after Chinese state-sponsored media outlet Xinhua placed ads targeting Hong Kong protesters. Twitter also suspended 936 accounts it said were part of a Chinese operation to “sow political discord in Hong Kong.” The new policy exempts taxpayer-funded outlets like NPR and the BBC. But it also exempts outlets like Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, both of which are funded by the U.S. government.

Why it matters: MIT Technology Review’s Angela Chen argues that the ban should also extend to VoA and RFE. She notes that, though there are differences between these outlets and Xinhua, any state-backed media “has enormous potential to influence public opinion and be abused, because governments have such deep pockets.”

What’s next: read on for more. While this week’s issue deals primarily with Facebook, it helps explain tech platforms’ reluctance to endorse or ban specific publishers.

And now, a look at Facebook’s complicated relationship with news.

Move fast and break news

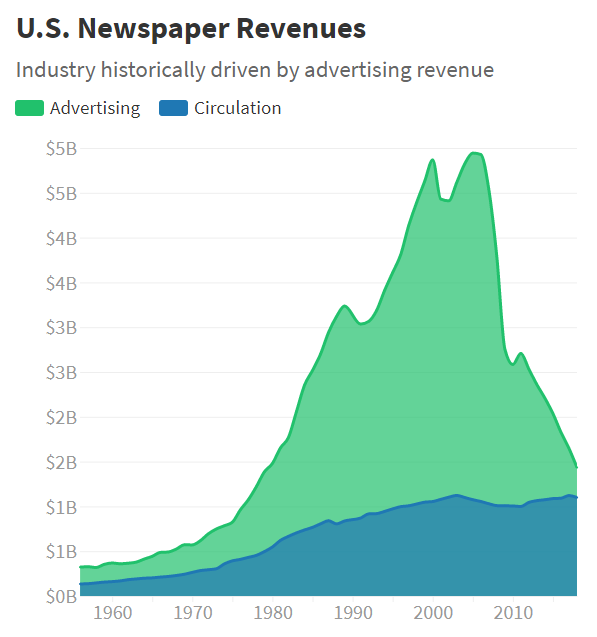

Historically, news publishers have relied mostly on ad revenue, and as a key gatekeeper between audiences and advertisers, they made decent money this way for years.

However, as more people flocked to sites like Google, Craigslist, Monster and Facebook, advertisers followed — and for good reason: these products provided better value than those offered by news publishers. They enabled advertisers to both reach wide audiences and narrowly target audiences that mattered to them, at a fraction of the cost. Also, unlike print newspapers, digital platforms weren’t bound by space limitations and could scale quickly.

As the digital economy transformed around them, many newsrooms proved either unwilling or unable to adapt. Politico senior media writer Jack Shafer observed that:

Where they gained monopoly power, which was most U.S. cities, daily newspapers gouged their classified customers pitilessly; they lobbied Congress heavily to block the early migration of classifieds to electronic forms. And the big newspaper chains helped destroy their own business by investing in national online classified advertising verticals, which they ultimately sold.

Obviously, news publishers were unsuccessful in fending off digital ad platforms. (And I can’t stress enough that these companies overwhelmingly make their money from ads — 98% of quarterly revenue in Facebook’s case).

Since then, the digital ad market has exploded — it’s now larger than the print and TV ad markets combined — but most of that new money went to Facebook and Alphabet (the parent company of both Google and YouTube), leaving news publishers struggling to find sustainable business models.

There is evidence that both Facebook and Alphabet engaged in anticompetitive business practices along the way, thus unfairly disadvantaging competitors (news publishers included). Regardless, publishers are understandably bitter that technology platforms siphoned so much of their ad revenue, and in doing so, redirected the flow of both money and information.

And that’s all before considering how Facebook tinkered with the News Feed.

News(?) Feed

The fundamental challenge with curating news content can be broken down this way:

A person can only consume a finite amount of news, but there’s virtually infinite news content available.

So, someone must decide which content to filter out, which to show and how to prioritize those stories.

In other words, someone must make editorial judgments about “better” and “worse” content.

Historically, that’s meant human editors at traditional news organizations, who (typically try to) prioritize content that’s factually accurate, unbiased, timely, important to the public, etc. But as more people turn to sources like Facebook, Twitter, Google, YouTube and Apple for their news, tech companies have become increasingly involved in making those editorial decisions.

Here’s the first problem with that shift:

Tech platforms, as for-profit companies, ultimately prioritize content that increases their bottom line.

In fairness, most of these companies are publicly owned, which means they have a legal obligation to make money for their shareholders. But the result is that the most influential gatekeepers of news content in the digital age — Facebook’s News Feed, Google’s search engine, Twitter’s timeline, Apple News — are operated by companies that, by design, put financial value over news value.

For Facebook, that means prioritizing content that keeps users on the platform longer and therefore leads advertisers to spend more.

Thus, the second problem:

Facebook has one News Feed where many different types of publishers compete for users’ attention.

Facebook alone has the power to decide whether the next post you’ll see will be your cousin’s baby pictures, Russian propaganda, or a story from MSNBC or Fox News. Mark Zuckerberg could wake up tomorrow, see how well those baby pictures are performing, and just decide to make Facebook exclusively baby pictures.

Good for babies, bad for news publishers.

Facebook hasn’t gone quite that far, but the mercurial nature of its News Feed algorithm has made it hard for publishers to build sustainable business models (take Mic, for example).

The un-pivot

When it first launched the News Feed in September 2006, Facebook took the most hands-off approach possible: reverse chronological order. That is, it decided the most important content — regardless of who published it — was simply the most recent content.

That approach evolved as Facebook searched for ways to better engage users. In October 2009, Facebook started using an algorithm to populate the News Feed, which it has repeatedly tweaked, each time making an editorial decision about which factors to give more (or less) weight to: recency, relevance, source, popularity, etc.

Sometimes, those tweaks helped publishers, like when Facebook introduced a tool that allowed them to reach audiences using filters like interests, demographics and location. In other cases, Facebook made wildly misleading promises. Most notably:

January 2014: Trending Topics

The pitch: Facebook created a feed that showed “viral” news stories, as determined by its algorithm, thus encouraging users to consume more news.

The reality: behind the algorithm were human editors who would reject or “inject” stories artificially. Former editors (anonymously) accused the team of bias against conservative viewpoints, and the ensuing PR headache led Facebook to shut down the feature (though other editors went on the record to refute those claims of bias).

May 2015: Instant Articles

The pitch: Facebook convinced publishers to host articles directly on Facebook. In addition to loading faster, Facebook said these articles would “give publishers control over their stories, brand experience, and monetization opportunities.”

The reality: publishers complained about a lack of monetization, control and data, while Facebook underreported traffic. Three years later, more than half of its publisher partners had abandoned the tool.

January 2015: Pivot to Video

The pitch: in a blog post, Facebook called video the “new universal language,” and said users were averaging 1 billion video views daily. Publishers invested heavily in video production, often firing reporters in the process.

The reality: it’s hard to overstate how disastrous the “pivot to video” was for publishers. Revenue from video content didn’t generate near the returns publishers had hoped for, leading to hundreds of layoffs. Publishers certainly bore some blame, but they crunched their numbers based on video view metrics that Facebook had dramatically exaggerated.

March 2016: Facebook Live + Facebook Watch

The pitch: attempting to compete in the livestreaming space, Facebook paid publishers including BuzzFeed, The New York Times, CNN, HuffPost, and Vox Media to produce live video content, and updated its algorithm to prioritize live streams.

The reality: the payments weren’t enough to make the new format worth it for publishers, and Facebook ultimately shifted focus again, this time to “longer, premium video content” via Facebook Watch, which many publishers didn’t have the resources to produce.

Finally, in January 2018, facing accusations of political bias and extensive issues with fake news, Facebook chose to back away from the problem by deemphasizing news entirely. Naturally, publishers were not happy. Buzzfeed’s Charlie Werzel had this observation:

In many ways, Facebook’s planned changes to News Feed are a retreat from the online public square the company helped create. They’re a tacit admission that the company’s great news experiment — which made it one of the most successful publishers in the world — failed.

Facebook isn’t unaware of its tumultuous history with the news industry. But its efforts to work with and support journalists, such as the Facebook Journalism Project, have been met with cynicism. When Facebook hired journalists to curate news, they described feeling dehumanized and disposable. When it tried to partner with fact checkers, the fact checkers eventually walked out. And when it couldn’t provide users with local news, citing a lack of local news outlets, The Guardian’s Julia Carrie Wong couldn’t help but notice the irony:

This brings us to Facebook’s latest effort to revive said corpse by paying publishers for content.

This time it’ll be different

Here’s what we know so far about Facebook’s latest initiative, thanks to reporting from The Wall Street Journal and Axios:

Facebook plans to create a dedicated “News Tab” that will exist separate from the News Feed where all publishers currently compete.

Facebook has offered to pay “dozens” of publishers up to $3 million annually — though it’s unclear how many total publishers would be included and how much Facebook would offer each.

The News Tab will also include content from “many” other publishers who won’t receive payments.

Facebook wants to make the News Tab “a personalized, highly relevant experience,” which likely means including a mix of national, local, and niche sources.

To do that, Facebook will primarily surface stories using “algorithmic selection,” but will also hire a small team of seasoned journalists to curate stories for a “Top News” section.

So, learning from its mistakes with Trending Topics, Facebook gives news its own home again, publishers get paid for their work, and quality journalism wins out over fake news and spam — sounds great, right?

Not so fast, say publishers, who are approaching things more cautiously this time around. Their biggest questions:

Where’s the money?

When Apple launched Apple News+, its “Netflix for news” service that similarly included payments for content, it angered publishers by taking a 50% cut and not sharing data. Unsurprisingly, publishers have reported that revenue from the deal has so far been “underwhelming.”

So, publishers want Facebook to make a more enticing offer, and they’re not yet convinced. As Damon Kiesow, a professor of journalism at the University of Missouri, pointed out:

$3 million is like a rounding error on Facebook’s part, so I don’t want to jump overboard and say it’s even that big of a change until we see the details.

How is Facebook picking winners?

Facebook has reportedly reached out to ABC News, Dow Jones (which owns the Wall Street Journal), the Washington Post and Bloomberg, but who else will be splitting the pot? Local news? Niche news? Partisan news?

Kiesow singled out the example of local news:

You could have easily 1,500 to 2,000 potential publications who you might consider would be able to provide quality local news. Three million divided by 2,000 is not a lot, and then it comes down to: [is Facebook] paying by volume of traffic, by volume of content, what is it?

It’s also not yet clear how Facebook plans to prioritize news stories, whether from paid or unpaid publishers. Ben Mullin, one of the reporters behind the original Wall Street Journal story, stressed the importance of Facebook’s human editors here, noting that:

Most of Facebook’s decisions with regards to hierarchy of content have been algorithmic, so it will be interesting to see whether Facebook invests in actual journalistic editorial judgment to make its News Tab something comparable to what you’d see at major news organizations or even at Apple News.

Axios’ reporting seemed to indicate that Facebook will hire editors, though it didn’t offer any details about the role they’ll play.

How hard will this be for publishers?

Nieman Lab staff writer Christine Schmidt said one of the main problems with Facebook Live was that it forced publishers to invest significant resources into creating new types of content. With the News Tab, she predicted publishers will wonder:

How much extra work do you have to put into it? Do you have to completely change your strategy and your employees and your hiring… or is this literally just clicking one extra button to send [a story] to the Facebook News Tab?

Mullin said that, at least so far, things look good for publishers on this front:

Facebook isn’t asking news organizations to create any content that they don’t already produce for this News Tab… so the amount of lift on the newsroom side isn’t a lot.

What is Facebook really up to?

When it comes to being honest about its intentions, Facebook doesn’t have a great track record. Zuckerberg claimed he wanted to create a space for trustworthy news, though Mullin said sources have told him they suspect Facebook has additional motivations.

Zuckerberg first teased the News Tab idea in April during a staged interview with Mathias Döpfner, CEO of Axel Springer (Europe’s largest publisher), just a week after Apple launched Apple News+. So, the most benign explanation is that Facebook simply wants to copy another competitor’s product, something it has done repeatedly.

But another possibility is that, as regulators increasingly talk about antitrust concerns, Facebook wants something it can point to as evidence that it’s not unfairly harming publishers (i.e. competitors). Kiesow argued that, barring a more substantial financial investment from Facebook:

The only explanation you can apply to it from a corporate perspective is that it’s crisis communications to try to build up their reputation, to try to fend off regulation, and that’s a political game.

The takeaway

It’s too early to tell whether a dedicated News Tab and content deals with a few dozen publishers will benefit news publishers or consumers. But this latest effort confirms that Facebook — specifically, its executives, engineers and editors — will continue to play an active role in controlling the news we see and who makes money producing it.

So, I’ll leave off with quotes from Schmidt and Kiesow that get at the inherent tension that will likely always exist between news organizations and digital ad companies like Facebook. As Schmidt put it:

[Facebook’s news initiatives are] a system for Facebook to include publishers in these trends in ways that are not necessarily long-term sustainable for the publishers, and they’re potentially just chasing the carrot.

According to Kiesow, that’s because:

[Facebook is] willing to work with [publishers] because [publishers] do have quality content and quality audiences, but [Facebook is] never going to behave in the way that a newspaper or a media company does, which is: the mission comes first, paying for the mission comes second.

Tech tip of the week: get f.lux, save your eyes

You’re probably aware that the blue light emitted by your screens can disrupt your sleep cycle. Avoid this by downloading f.lux, a free app that adjusts the tint of your screen throughout the day:

Next week on Trusty: capitalism gets woke

The Business Roundtable, a who’s who of 181 CEOs, is rethinking what it means to be a corporation in 2019. We’ll look at what prompted this pivot and what it means for businesses, executives, employees, consumers and investors.

As always, subscribe and share if you haven’t already!