Hey Trustees!

The 2020 presidential candidates have repeatedly taken aim at big tech, threatening to regulate it every which way. But who's even policing the industry today and how are they doing?

In this week's issue, we'll take a look at one of tech's top cops, the Federal Trade Commission, and what it does (or doesn't do) when companies act up.

But first, some news:

Guns are not a platform problem

Article: Casey Newton / The Interface

What happened: people are reeling from two mass shootings this weekend — one in El Paso, Texas, and another in Dayton, Ohio. Much of the news coverage has focused on the role that online forum 8chan played in enabling the El Paso shooter to disseminate his manifesto. Casey Newton, who covers social media platforms extensively in his daily newsletter, pointed out that the availability of guns and the country’s long history of racism are not these platforms’ fault.

Why it matters: it’s easy to pile on tech companies, and indeed there’s a need for more critical (and nuanced) conversations around exactly how responsible companies should be for content spread via their platforms or using their technologies. But Newton’s take is a good reminder not to let those conversations drown out the underlying issues.

What’s next: in his nationwide address Monday, President Trump outlined several potential policies to address the gun violence epidemic. The BBC has this helpful rundown evaluating the practicality of each.

De-bot-able

Article: Maureen Linke + Eliza Collins / WSJ

What happened: data from social media analytics company Storyful showed that hundreds of bot-like Twitter accounts spread misinformation during the Democratic primary debates, specifically around racial issues and Sen. Kamala Harris’ ethnicity.

Why it matters: one commentator’s tweet got over 12,000 retweets, largely attributable to bot-like accounts, showing how far this sort of misinformation can reach in a short amount of time. It also highlights the difficulty in detecting it — this bot network was found by a company intentionally looking for suspicious traffic, meaning social media users who encountered these tweets likely had no idea they were interacting with bots.

What’s next: discomforting as this sounds, we don’t really know. Recode’s Emily Stewart put the dilemma this way:

It’s not just the misinformation itself that sows division, it’s also the debate about it. People are confused about what social media manipulation is, how it works, and whether it’s happening.

FTC Inefficacy

#Techlash2020

Though big tech escaped from last week’s debates largely unscathed, the Democratic primary candidates have generally been critical of the industry. They’re not out of touch on this issue, either. Just half of Americans believe tech companies are having a positive impact on the direction of the country, down from 71% four years ago.

Several candidates, namely Elizabeth Warren, favor breaking up major companies like Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Alphabet Inc. (the parent company of Google and YouTube). Some, such as Cory Booker, take issue with corporate consolidation more broadly. Others believe the solution lies in doing a better job of enforcing existing laws (the New York Times has a handy rundown of their positions).

Regardless of what solution they propose, all seem to agree there’s a problem with the way tech companies are policed now. Unfortunately, the term “regulation” carries a lot of baggage — for free-market types, who would rather government stay out of things, and for people generally, who associate regulation with dull bureaucratic processes and simply tune out.

But if you’re one of the many voters — Republican or Democrat — who want the nation’s next chief executive to crack down on the industry, it’ll be difficult to choose between the two dozen options without understanding a bit about tech’s current regulators. Fortunately, there’s a lot to be learned just from looking at one agency in particular: the Federal Trade Commission.

The FTC has made headlines recently for its $5 billion settlement with Facebook, $575 million settlement with Equifax and newly launched investigation into the tech industry’s data practices. Casual observers may view that as a sign the FTC is being aggressive in its watchdog role. But many critics point to those same headlines as evidence that the agency is asleep at the wheel.

So, without getting too deep into the weeds, today’s issue will try to demystify the FTC’s role in the “techlash” conversation.

An (anti)trusty agency

Understanding the environment in which the FTC originally emerged is crucial because we’re seeing similar economic trends today. In 1890, responding to concerns about the extreme economic power wielded by large trusts like Standard Oil and U.S. Steel, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, which prohibited certain business practices and arrangements that harmed consumers, such as trusts, monopolies and cartels.

However, courts said the law didn’t apply to mergers or acquisitions, and companies adapted, triggering a wave of consolidation that ultimately limited the law’s impact. So, in 1914, Congress responded by introducing additional protections via the Clayton Act and by creating the FTC to enforce its provisions.

Congress gave the FTC broad authority to:

Prevent anticompetitive, deceptive and unfair business practices

Seek financial compensation for consumers harmed by such practices

Write rules specifying those practices and deterring companies from using them

Investigate businesses and their managers to ensure they’re acting in legitimate ways

Report findings, research and legislative recommendations to Congress and the public

Each one of these functions is meant to help the agency ensure businesses don’t act in ways that harm consumers OR unfairly reduce competition in the market — across all industries. But a century into the FTC’s existence, carrying out its mission has proven easier said than done.

Politics as usual

The FTC’s dual mandate to prevent consumer harm and promote competition is reflected in the agency’s structure (which I’ve simplified below for our purposes, see the full version here):

However, politics are also built into the FTC’s structure. Its five commissioners are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate (similar to Supreme Court justices), each serving seven-year terms. No more than three can be from one party, but that still means a majority come explicitly from one side of the aisle.

And yes, the commissioners’ political ideologies do shape the agency’s actions.

In 1969, noted consumer advocate Ralph Nader enlisted seven law students, dubbed “Nader’s Raiders,” to conduct a review of the FTC. They released the influential “Nader Report on the Federal Trade Commission,” which called out the agency for being overly cozy with both business and Congress.

Then, under the Carter administration, the FTC drew ire for its perceived overreach and activism, culminating with its efforts to regulate TV advertising to kids. That led Congress to cut the agency’s budget and even shut it down for a day. Conversely, the Reagan administration’s FTC sought to compromise and cooperate with business rather than stick companies with tough penalties, and its chairman sought to reduce the agency’s rulemaking role.

Al Kramer, who led the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection from 1977 to 1981, said that, since his time at the FTC, “the atmosphere has gotten much much more partisan.” Kramer attributed that polarization to an increasing number of agency officials coming from Capitol Hill — that is, from a political rather than an administrative, legal or technical background.

Out of commission

Party politics only tell part of the story, however. The Nader Report, while pointing out the agency’s political conflicts, aimed its strongest criticisms at much more basic structural problems. It found that the FTC:

Relied too heavily on consumers to identify violations by companies, making it slow to respond;

Failed to set priorities for its enforcement work, focusing on trivial matters instead of serious harms;

Was too reluctant to go after large companies, too willing to lean on toothless “voluntary” compliance actions, and too unwilling to hold businesses accountable for violating those actions;

Avoided transparency at all costs, potentially to mask its collusion with businesses;

Didn’t make use of its existing resources and enforcement authority AND didn’t ask for the additional resources and authority it really needed; and

Lacked staff with technical expertise — that is, engineers and doctors in addition to lawyers.

Basically, according to the report, the agency was underfunded, underresourced, unmotivated, opaque, and too friendly with both business and Congress.

So why are we talking about a report that Ralph Nader and some law students wrote as part of a summer job 50 years ago? Because these same issues are preventing the FTC from meaningfully regulating the tech industry today. Just last month, Nader wrote to the agency’s commissioners, saying:

The FTC remains a largely moribund, sluggish, frightened, alleged watchdog for the American consumer. Institutionally, it has an anemic estimate of its own significance during this wave of corporate crime, fraud and abuse. It raises few general alarms about grave harm to consumers and has dropped the ball, with its Justice Department counterpart, on antitrust enforcement, to an extreme degree.

A few of his specific critiques:

The FTC’s delay in addressing consumers’ complaints is, essentially, a hallmark of its brand

The FTC is intimidated by an “industry-indentured” Congress (i.e. special interests)

Its budget is “disgracefully small”

In response to the FTC’s $5 billion fine against Facebook for violating previous FTC enforcement actions: “the stock market and Facebook are laughing at you”

Notice any similarities?

Nader isn’t alone in his assessment of the agency. Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization, published a report earlier this year detailing the FTC’s extensive revolving door problem over the past two decades. It found that:

76% of top FTC officials worked — either immediately before or after their agency tenures — for corporate interests, consulting them on FTC issues.

63% had conflicts of interests specifically within the tech industry, including:

100% of Bureau of Competition directors, and

57% of Bureau of Consumer Protection directors.

Matt Stoller, a fellow at Open Markets Institute, an increasingly influential think tank focused on corporate concentration and monopoly power, was more direct about how that has corrupted the agency:

They don’t do their job. They don’t investigate. I don’t believe them. They don’t have credibility.

Stoller told me this in response to a question about the FTC’s recent settlement with Facebook, which prompted a similar outcry from other tech critics. Since it highlights many of the above issues in the context of regulating big tech, I want to end this issue by talking about why those critics were so up in arms — and why investors were ecstatic.

Haven’t we FTCeen this before?

First, a brief recap of what this whole case was about. In March 2018, The Guardian reported that Cambridge Analytica had improperly bought data on millions of Facebook users from a third-party app developer in violation of Facebook’s own rules. Shortly after, the FTC opened an investigation into the company’s data privacy practices, which eventually expanded to include its numerous other privacy scandals.

Importantly, Facebook already had a history with the FTC: in 2012, it entered into a “consent decree” with the agency for misleading users about the privacy of their data. That agreement prohibited Facebook from, among other things, further misleading users.

A full year later, the FTC’s investigation ultimately found that Facebook “repeatedly used deceptive disclosures and settings to undermine users’ privacy preferences in violation of its 2012 FTC order.”

F’d by FB

So, what’s Facebook’s punishment for being a repeat offender? A record-setting $5 billion fine, increased oversight and “significant new privacy requirements.” Both the FTC and Facebook want people to believe that’s a really big deal.

But most observers didn’t seem to agree with their assessment — not the two dissenting FTC commissioners, not ex-FTC officials, not lawmakers, not the media, and most importantly, not Wall Street.

Former FTC chief technologist Ashkan Soltani had this reaction:

How come? There are a few key reasons why people believe the FTC let Facebook off easy:

Weak investigation

Despite taking more than a year, the FTC left some serious stones unturned:

Zuckerberg and other Facebook executives escaped the hot seat: Jim Kohm, the FTC’s lead investigator on the case, acknowledged this was out of convenience, saying Facebook’s lawyers were worried Zuckerberg would be exposed to legal liabilities if the FTC deposed him and that the FTC could resolve the case quicker by just skipping that step.

“Blanket immunity”: FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra, who dissented in the case, called out the agency for its unusual decision to give blanket immunity to Facebook executives for “unspecified violations” — that is, Zuckerberg and others get a pass for any past data privacy sins we haven’t yet learned about.

The FTC’s revolving door struck again: Facebook’s lead counsel in the case, M. Sean Royall, used to work at… you guessed it: the FTC (directly under current FTC chairman Joe Simons), casting further doubt on the idea that the agency was sufficiently tough.

Weak penalties

Let’s assume momentarily that the FTC really did look into every angle of this case and that there was no additional wrongdoing on Facebook’s part. The FTC still said Facebook repeatedly violated its legal obligations and deceived consumers, yet did little to deter future bad behavior:

Facebook can keep collecting all the data it wants: the settlement does not force any changes to the business models and practices that incentivized Facebook to violate users’ privacy in the first place. Instead, it allows Facebook to continue full steam ahead, so long as it maintains a paper trail and gets sign-off from privacy overseers with no authority to hold it accountable.

No repercussions for Facebook executives: both Chopra and fellow dissenting Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter believed the FTC had sufficient evidence to specifically name Mark Zuckerberg, and possibly others, in litigation. Such a move could have carried actual consequences, causing executives to tread more carefully in the future, but Chairman Joe Simons said the agency opted not to go this route because it worried about losing in court.

$5 billion is nothing to Facebook: the same day the FTC announced the settlement, Facebook reported that it raked in nearly $17 billion in revenue last quarter. That is, it made enough money to pay off the fine in under four weeks. In the FTC’s second-largest data privacy settlement, it fined Google $22.5 million, but crucially, that amounted to five times as much as Google made off its deceptive practices. It’s possible Facebook made much more than $5 billion off the data it collected.

What’s the takeaway?

As per usual, it comes down to money. From Chopra’s dissent:

Breaking the law has to be riskier than following it. As enforcers, we must recognize that until we address Facebook’s core financial incentives for risking our personal privacy and national security, we will not be able to prevent these problems from happening again.

With its settlement, the FTC failed to make the cost of breaking the law outweigh the financial benefits — and investors knew it.

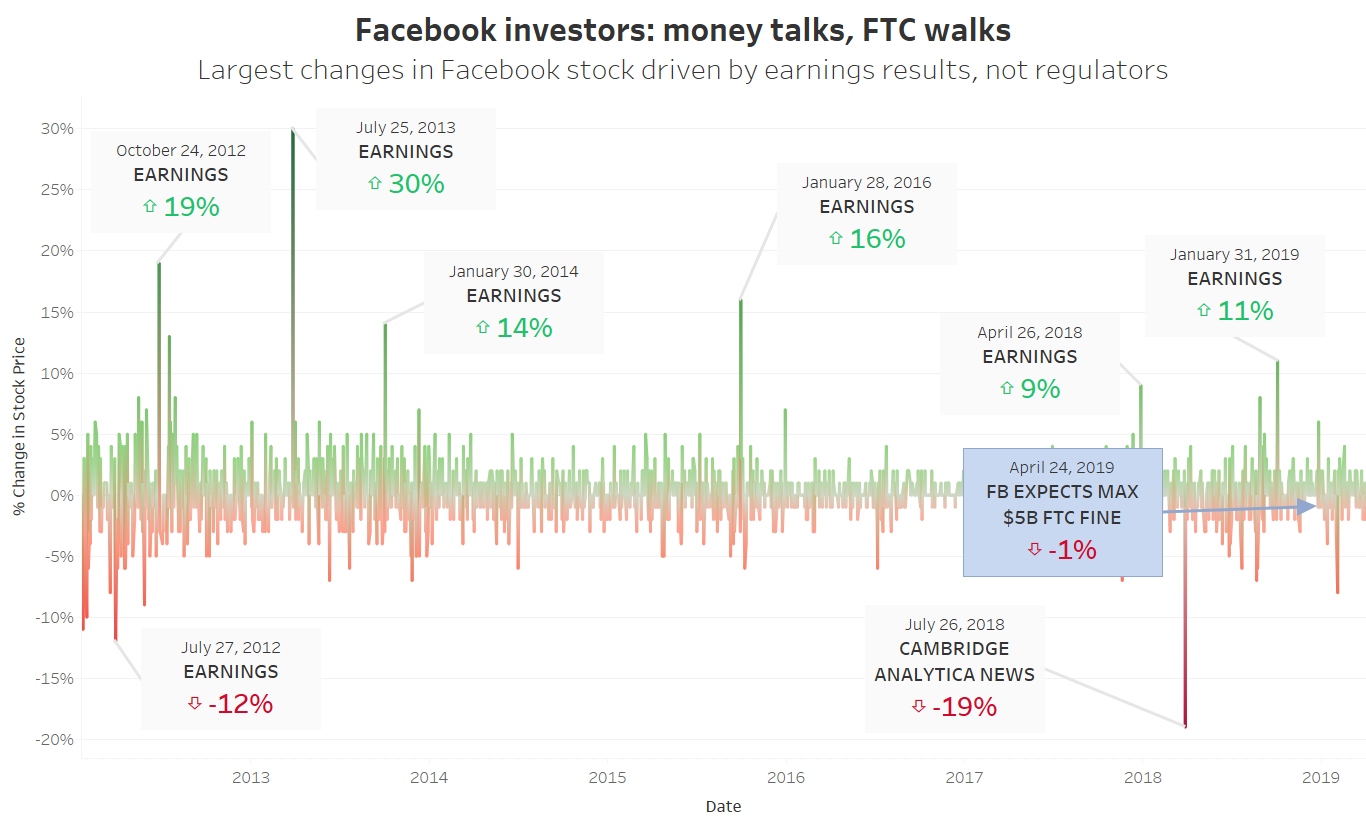

When Facebook first told investors back in April that it expected a maximum fine of $5 billion, its stock only took a 1% hit. And when news of the settlement broke in July, shares in Facebook actually went up (Zuckerberg’s shares alone increased in value by roughly $1 billion). During Facebook’s latest earnings call, one analyst even told executives, “good news on the FTC settlement.”

In fairness, the FTC’s goal isn’t to tank a company’s stock. But consumers should be able to trust it to deter companies from doing things that harm them, and if the deterrent causes the market to reward a company for bad behavior, it’s not much of a deterrent.

However, as The Verge’s Makena Kelly noted:

Most of what critics want — higher fines, personal liability, hard limits on data sharing — couldn’t be obtained through a settlement. Facebook simply wouldn’t agree to it. The only way to get it was by going to trial, which the FTC wasn’t ready to do. The courts are unpredictable, the majority said, and the Commission perhaps wouldn’t have received the amount of relief that was agreed to in the settlement.

So, if the chief tech regulator doesn’t wield enough power to effectively police Facebook, but can’t turn to courts out of fear they’ll do even less, where does that leave things?

Guess you’ll have to check back next week to find out.

As always, let me know what you think here:

And share and subscribe if you haven’t already!