WillWeWork?

Is We Co. a real estate or tech company? Investors seem to think it's the former — and not a good one at that.

Welcome to Trusty, a weekly newsletter exploring how technology is changing the ways people build trust online by guiding you through the top headlines from Silicon Valley, D.C., Wall Street, Brussels and beyond. Subscribe below to get future issues delivered straight to your inbox.

Hey Trustees!

This week, The We Company (parent company of WeWork) dominated the tech news cycle. Three key storylines:

We Co. postponed its planned IPO amid investor concerns over its valuation, business model and governance structure.

A Wall Street Journal profile of founder and CEO Adam Neumann detailed his “unusual exuberance and excess,” which investors increasingly view as a liability.

A CNET investigation exposed major security issues with WeWork’s WiFi networks, which considering We Co.’s efforts to position itself as a tech company, could give investors additional reason to worry.

More on why this matters below, but first some additional headlines:

Mark Zuckerberg returned to Capitol Hill for the first time since his highly publicized testimony in April 2018. A Facebook spokesperson said Zuckerberg set up private meetings with various congressional critics to discuss “future internet regulation," while lawmakers characterized the powwows as opportunities to “air their grievances about the company's conduct.”

Cristiano Lima / Politico

Lawmakers grilled big tech representatives over allowing extremist content to spread on their platforms. During a Senate Commerce Committee hearing Wednesday, policy executives from Facebook, Google and Twitter pointed to “proactive measures” they’ve taken using AI tools. However, The Hill’s Harper Niedig noted that tech companies are up against opposing criticism from each side of the aisle:

“Democrats have pushed them to crack down more forcefully on white nationalist extremism, while Republicans have leveled unproven allegations that social media companies are censoring conservative voices.”

Senate Leader Mitch McConnell agreed to allocate $250 million for election security, despite years of resisting proposed legislation from Democrats. Conservative political activists held a press conference Wednesday calling on McConnell to act. That comes as Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Jack Reed (D-R.I.) introduced a bill this week aimed at combating foreign election interference by improving intelligence sharing and requiring campaigns to report contact with foreign nationals.

Joe Uchill / Axios | Maggie Miller / The Hill

Facebook introduced the next generation of its Portal video chat devices amid privacy concerns, doubling down on its expansion into smart display hardware. However, Bloomberg reported Wednesday that Facebook contractors will listen to some user audio collected by the devices, despite the company announcing it had abandoned human review of audio back in August. Apple, Google and Amazon have also faced scrutiny over the practice in recent months.

Kurt Wagner + Mark Gurman / Bloomberg

Trump quietly attended a fundraising event in Silicon Valley, which organizers worked hard to keep under wraps, highlighting the difficulty Trump has had in recruiting supporters from the tech industry. The Wall Street Journal reported that former Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy hosted the event.

Rebecca Ballhaus + Chad Day / WSJ

Facebook’s former policy chief and “fall guy” Elliot Schrage still hasn’t left the company, despite announcing his resignation over 15 months ago. Schrage ostensibly resigned to take heat off the company as it faced criticism over its response to numerous scandals, including hiring an opposition research firm to investigate George Soros. However, Bloomberg reported that Schrage has remained involved in day-to-day Facebook operations.

Kurt Wagner / Bloomberg

Airbnb announced in a press release today that it plans to become a publicly traded company in 2020. The New York Times reported that Airbnb is exploring nontraditional approaches to its IPO, taking a cue from tech giants Spotify and Slack, both of which opted for direct listings earlier this year. Direct listings allow companies to bypass the step of raising additional capital from large institutional investors.

Erin Griffith / New York Times

AT&T is considering dropping DirecTV, which it bought in 2015 for $49 billion. The news comes on the heels of a report from activist investor Elliott Management that criticized AT&T’s acquisition strategy and would mark a sharp reversal for the telecom giant.

Shalini Ramachandran + Drew FitzGerald / WSJ

California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill into law that could force many companies to reclassify workers as employees rather than independent contractors. The bill was aimed specifically at gig economy companies Uber and Lyft, which Newsom’s office said had used contractors to avoid offering “basic worker protections like the minimum wage, paid sick days and health insurance benefits.” However, things are unlikely to end here — Uber’s top lawyer has already argued that the new law doesn’t apply to Uber drivers — and will probably involve ongoing negotiations between the affected industries, labor groups and lawmakers.

Margot Roosevelt + Johana Bhuiyan + Taryn Luna / Los Angeles Times

Apple’s $14 billion EU tax penalty got its day in court this week as the EU General Court weighed the merits of rulings from the European Commission (headed by EU competition chief Margrethe Vestager). As Politico noted:

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of these court proceedings for Vestager because her steely reputation is heavily invested in the radical strategy of defining countries' tax deals for multinational companies as illegal subsidies.

However, the Wall Street Journal also pointed out that Apple loses either way, as it would end up owing taxes to the IRS instead of the EU if the court rules against it.

Simon Van Dorpe / Politico EU | Rochelle Toplensky / WSJ

Vestager said the EU may impose new data privacy rules on tech companies, hinting at how she might use her new regulatory powers to crack down on intrusive data collection practices. “If we want to define the market, to set out what’s acceptable and what isn’t, then what we need is not more competition enforcement. We need regulation,” Vestager said.

Foo Yun Chee / Reuters

WillWeWork?

The background

Tuesday: The We Company postponed its initial public offering, facing a cold reception from investors concerned over the real estate company’s valuation, business model and governance structure.

Wednesday: a Wall Street Journal profile of founder and CEO Adam Neumann claimed the “combination of entrepreneurial vision, personal charisma and brash risk-taking” that initially helped Neumann lure private investors has now become a liability in the eyes of public market investors.

Thursday: a CNET investigation resurfaced concerns over the lack of security on WeWork’s WiFi networks, which have been exposing tenants’ sensitive documents since 2015.

What even is a tech company anymore?

We Co. has worked aggressively to position itself as a disruptive tech company that wants to change the world, because tech startups have historically enjoyed much higher valuations from investors. The theory is that these companies can grow faster, cheaper and/or larger than conventional companies, and thus generate much higher returns (think Facebook vs. White Pages, Amazon vs. Walmart, Uber vs. taxi companies, Airbnb vs. hotels, etc.).

For awhile, We Co.’s investors bought that pitch. Softbank, a massive venture capital fund, has put more than $10 billion into the company and valued it at $47 billion earlier this year. But as they’ve learned just how much money it’s losing, investors have become less convinced that We Co. is actually a tech company deserving of that inflated price tag. As a result, We Co.’s latest valuation is reportedly down to around $10 billion.

The WeWork business model is hardly innovative: it takes out long-term leases on office buildings, spruces them up and subleases them to individuals and companies at a higher rate. We Co. claims that it does this more efficiently than other real estate companies by automating the design and construction process, applying data science when selecting locations, and using machine learning to set pricing. We Co. did attempt to expand beyond co-working, but its $164 million investment in other ventures last year only brought in $124 million, and its failure to implement basic WiFi security doesn’t help its efforts to brand WeWork as a “space-as-a-service” product.

Ultimately, leasing real estate is expensive: We Co.’s public filings indicate it’s currently on the hook for $47 billion in lease obligations, while the revenue it generates from renters isn’t keeping pace. Real estate is also vulnerable to downturns in the market, and investors worry We Co. could get stuck with those lease obligations if customers aren’t able to continue renting turning a recession.

Finally, WeWork spaces can’t scale overnight. With a company like Airbnb, new users simply need a smartphone to access its platform — Airbnb doesn’t need to invest significant additional capital to add new properties to its portfolio. WeWork, on the other hand, must identify, lease and furnish new spaces — a more time and capital intensive process.

Much of We Co.’s advantage so far has come from its ability to raise massive amounts of VC funding, thus enabling it to expand its footprint faster than it could otherwise. But We Co.’s attractiveness to investors relied significantly on Neumann’s ability to sell We Co. as a disruptive tech company aiming to tackle markets beyond real estate. With recent public filings suggesting that vision could be harder to reach, investors have soured.

Founder worship

Silicon Valley investors have historically embraced (typically male) founders with eccentric personalities, even when their leadership styles have at times created problems — think Steve Jobs, Travis Kalanick, Elon Musk and Elizabeth Holmes, among others. Investors buy into the founder’s vision, drive and charisma and, eager to get in early on a hot tech company, agree to a deal where the founder keeps majority ownership over the company.

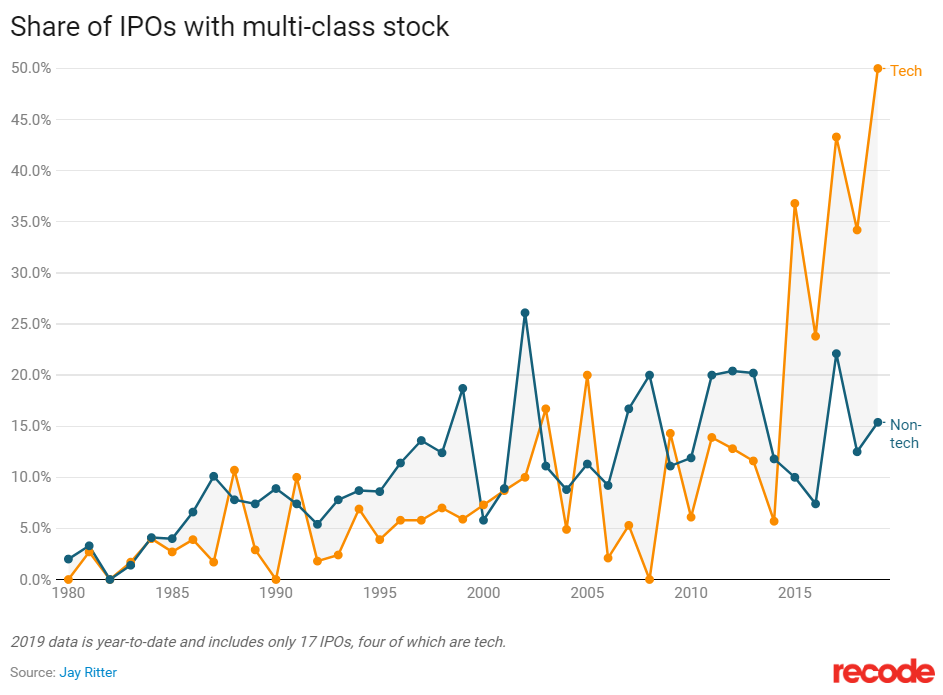

But tech founders have often leveraged investors’ deference to retain control even after going public. By issuing themselves a special “class” of shares with disproportionate voting rights, founders ensure they retain a majority of votes even if they only own a minority of the company financially. Alphabet, Facebook, Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Snap, Pinterest, Blue Apron and Stitch Fix have all used this approach, and tech companies in general have made more use of multi-class share structures.

However, investors’ blind trust in founders has waned in recent years. Facebook shareholders, concerned that Mark Zuckerberg may not be leading the company in the best direction, have repeatedly attempted to rein in his power by changing the share structure. After besieged Uber founder Travis Kalanick resigned his position as CEO, the company’s board reduced the voting rights of his shares in order to regain control of the company. And Elon Musk has gotten Tesla into trouble with the SEC on multiple occasions over tweets, much to the dismay of investors.

While many tech founders still enjoy broad deference, Adam Neumann’s track record of self-enrichment and We Co.’s numerous conflicts of interests has public market investors worried. Former Twitter CEO Dick Costolo told the Wall Street Journal:

“The degree of self-dealing in [We Co.’s public filing] is so egregious, and it comes at a time when you’ve got regulators and politicians and folks across the country looking out at Silicon Valley and wondering if there’s the appropriate level of self-awareness.”

The takeaway

It’s unclear at this point when (or if) We Co. will move forward with its public offering, and VCs have cautioned against drawing broad conclusions about tech IPOs considering the company’s relatively unique situation. However, the prospects of tighter regulation of the tech industry, a looming recession, and increased skepticism of the “founder-knows-best” status quo mean that tech companies could face lower public valuations going forward — or at the very least, be forced to adopt governance structures that are less favorable to founders.

If you enjoyed Trusty or think someone you know might, please subscribe and share below! Thanks for reading and stay tuned for next week’s issue!